The cocktail shelf is getting crowded! We wrote last month about two Negroni books; we've got books galore about seasonal cocktails lying around from national stars like Katie Loeb and local cocktail mavens like Maggie Savarino. There isn't a self-respecting saloon in Seattle that doesn't have a "Craft Cocktail" list to upsell from a vodka-tonic to some lavender-infused concoction that takes ten minutes to prepare.

The cocktail shelf is getting crowded! We wrote last month about two Negroni books; we've got books galore about seasonal cocktails lying around from national stars like Katie Loeb and local cocktail mavens like Maggie Savarino. There isn't a self-respecting saloon in Seattle that doesn't have a "Craft Cocktail" list to upsell from a vodka-tonic to some lavender-infused concoction that takes ten minutes to prepare. Then you've got all the producers of specialty liqueurs (St. Germain, to name just one) with recipe books of their own. A home bartender can get seriously ivolved with do-it-yourself bitters, homemade syrups and pickled garnishes. And the mixologists! A regiment of "behind-the-bartists" eager to show off their inventiveness.

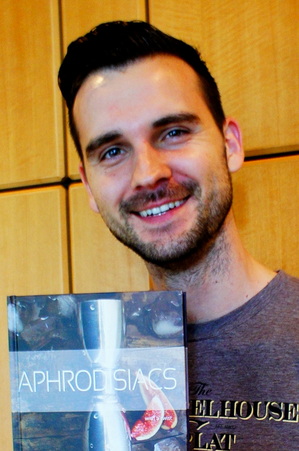

Here's one of the best: Mark Sexauer, an award-wnning professional bartender, Seattle-based brand ambassador for Bacardi, who has turned a hundred or so original drink recipes into a handsome hardcover book titled Aphrodisiacs With a Twist. The book's premise is the well-known observation that alcohol is a social lubricant that can "elicit and heighten the sexual experience."

For example, Sexauer's take on the classic Manhattan, which he calls "Tastes Better in Bed," substitutes a homemade reduction of red wine and lime leaves for the traditional vermouth, then adds a splash of orange cordial and a dash of chocolate bitters. Then there's the "Bastadro," which takes four ingredients, including a sweeter red wine syrup, a vermouth called Cocchi Americano and tequila.

Nothing particularly aphorodisiac there? Try this: the Roy and Gouda.

Many cheeses, Sexauer points out, "can resemble the scent of a woman and can be stimulating for both sexes." The active ingredient is phenlethylamine (also found in chocolate, by the way), which is related to the release of endorphins. Here's where it gets all Modernist: Sexauer makes a foam with smoked gouda, olive oil and heavy cream, pours the mix into a nitrous oxide canister to freeze it, then squirts fanciful shapes onto a baking sheet. As you drink the cocktail (a scotch & vermouth concoction resembling a Rusty Nail), the cheese begins to thaw. "It should be the last thing you taste."

The photographs, by Charity Lynn Burgraaf, (styled by Kimberly Swidelius) do a great job of highlighting the color or key ingredients of the cocktails.

Aphrodisiacs with a Twist, 256 pages, $24.95