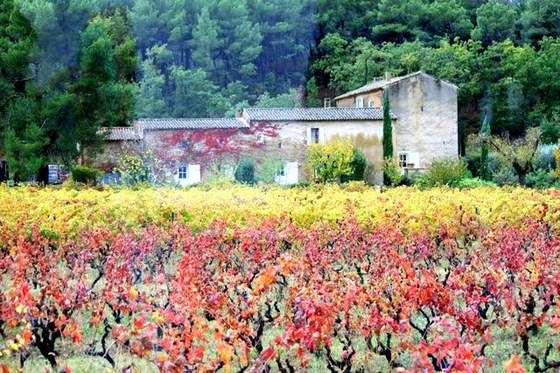

In the mid-80s, one spring afternoon, I stood in a magnificent vineyard overlooking the Loire Valley in the Savennières appellation of central France, listening to a mild-mannered investment banker turned gentleman farmer (corduroy work pants, dress shirt, well-worn blazer) talk about cow horns and phases of the moon to explain what he was doing to his mother's vineyard. It made little sense to me at the time (and I was not alone, believe me), but the wine itself, La Coulée de Serrant, was incredibly focused, an expression of chenin blanc that I had never tasted. Similarly impressed two decades later was the distinguished wine journalist Robert Camuto, who devotes a chapter to Joly

in his book about independent thinkers in French wine country,

Corkscrewed.

In the interim, Joly has become the guru of the biodynamic winemaking movement. His book,

Le Vin du Ciel à la Terre (Wine from Sky to Earth), has been translated into nine languages. He describes the four tragedies of modern agriculture (herbicides, chemical fertlizers, interfering with the vine's sap, and "technology" generally--commercial yeasts specifically) that replace the grape's natural flavor with genetically engineered substitutes.

And Joly, for his part, had fallen under the spell of Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian cultural philosopher who attempted to reconcile science and mysticism, and, in 1924, came up with the concept of biodynamic agriculture. (Earlier, Steiner had developed the theoretical basis for the Waldorf schools; he also wrote plays and political books. Hitler attempted to discredit Steiner, after his death in 1925, because he called for better treatment of Germany's and Austria's Jewish citizens. Biodynamic practices were banned under the Nazis.) But in the last decades, Steiner's agricultural manifesto has taken on a life of its own, especially among the most elite wine growers.

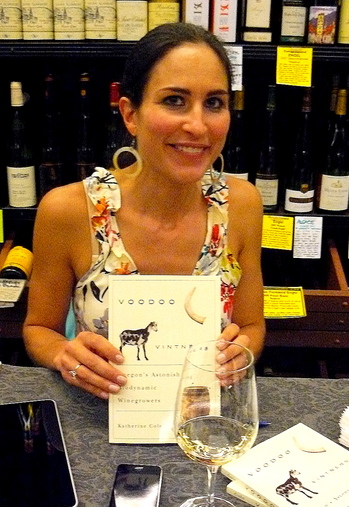

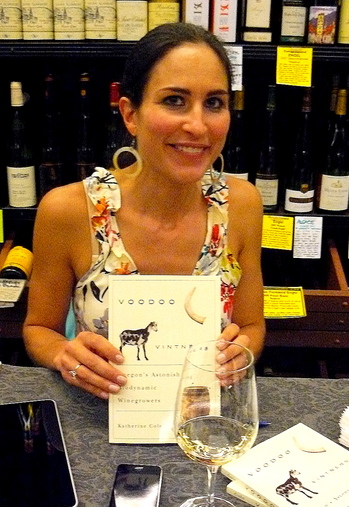

In addition to Joly's Coulée de Serrant, several of the leading vineyards in Burgundy, the famous Domaine de la Romanée-Conti among them, converted to biodynamic viticulture, and in the summer of 2001 the DRC's feisty, diminutive co-owner Lalou Bize-Leroy arrived at Linfield College in McMinnville, Ore., to address the annual meet-up known as the International Pinot Noir Celebration. The scene is recounted in detail by Katherine Cole in

Voodoo Vintners, her new book about biodynamics in Oregon.

Within weeks of Bize-Leroy's talk, several wineries began incorporating biodynamic practices in their viticulture, and six months later the indusry established a formal biodynamic study group. The

Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association made Oregon its home, and

Demeter, an international organization that actually owns the trademark of the term biodynamic, and has the exclusive right to certify farms as biodynamic, has since established its American headquarters in Philomath, Ore.

Seattle-born Cole, who now lives in Portland and writes about wine for

The Oregonian, takes her readers on a guided tour of vineyards run by cast of Carhartt-wearing characters. They may only farm five or six percent of the state's vineyards, but they produce an outsize share of its best wines, especially the elusive pinot noirs for which Oregon has become famous. Many of the practitioners come to the wine-grower lifestyle with what Cole calls "good genes, good fortune, good work ethic and good credit," the good credit being particularly important, in my view, in an industry with 800 competitors state-wide. (When I wrote the first guidebook to the nascent Oregon wine country in 1981, it proudly proclaimed to cover "All 37 Wineries"!) So far, 68 vineyard properties in the US are Demeter-certified, 16 of them in Oregon.

So what's the point of biodynamic, or BD (as it's called)? Above all, it's a respect for the land and its connection to the cosmos.

Prior to the original planting of a conventional vineyard, Cole points out, earthmoving equipment uproots trees, bushes and boulders, then smooths the soil. Weeds sprout among the vines, so the grower spreads herbicide, which kills off benign cover crops that might restore nutrients to the soil. Meantime the roosting spots for birds and insects have been bulldozed, so there are no longer any owls to eat gophers or birds to eat larger insects. This calls for pesticides, which in turn curtail the aerating and phosphorus-releasing capabilities of earthworms. Fungi move in, the dirt gets rock-hard, lifeless and brittle; the farmer tills the rock-hard soil, dispersing dust and whatever organic matter was left. Without humus to store moisture and nutrients in the topsoil, the vine droops, gets sick and attracts pests, for which the conventional solution is, you guessed it, chemical fertilizers, "a steroid shot straight to the vein of the plant, pumping it up for now but setting it up for a future heart attack or stroke."

True believers have several homeopathic remedies: Preparation 500 (a cow horn packed with the manure of lactating bovines), Prep 501 (a cow horn packed with ground quartz); 502 involves yarrow flowers, 503 camomile, 504 stinging nettles, 505 chopped oak bark, 506 dandelions, 507 valerian, and 508 a giant cauldron of tea steeped from horsetails rich in silica. There are strict prescriptions as well for their application (burying the cow horns in the vineyard during specific phases of the moon among them). But how much of this is legit, how much is quasi-religious ritual, how much of it is voodoo?

Matt Kramer, the conscience of Oregon's wine industry, thinks of BD as a sort of kosher practice. Steiner himself modeled his theology on the Zoroastrianism of ancient Persia. But lunar planting cycles are paleolithic, recognized in Mesopotamian times, and well understood by farmers of medieval Europe. "Agricultural engineering" was originally part of the industrial revolution in England (a market for threshing machines to replace the farmhands who'd gone off to factory work in the cities), but everything changed with the advent of the First World War and the appearance of synthesized ammonia that could be used as an explosive or as fertilizer. In post-war Europe, Steiner's voice was a lonely, though not entirely solitary exortation, against "progress." (Hermann Hesse was an ally.)

So by the time all this gets down to Oregon, what do we have? Consultants, for starters. True believers, it goes without saying. Neighbors who roll their eyes. But nothing really unusual. "Biodynamic farming," says pioneer Bill Steele, owner of Cowhorn Vineyards in Jacksonville, Ore., is 60 percent canopy management, 30 percent tillage and 10 percent everything else." As Cole says, that's about as banal as it can get.

The voodoo isn't far away, though. Kevin Chambers, who runs Oregon Vineyard Supply as well as Results Partners LLC, sticks a vertical 8-foot piece of PVC pipe in his vineyard; inside is a copper coil. "It's a radionic field broadcaster," he tells Cole, without a trace of irony.

Not surprisingly, there's a

blog devoted to debunking BD. It's "bad science," says its author, a California wine grower named Stu Smith, who supports sustainable organic farm practices instead.

"Those who don't understand biodynamics--and don't understand voodoo," writes Cole, "use the term in reference to the preparations: the buried cow horns, the hanging stag's bladders...they're thinking Louisiana voodoo." But in fact it's more like Haiti's voodou, a nature-worshipping belief system, not agricultural but spiritual. Are its viticultural practitioners batshit crazy dreamers or brilliant wine makers?

Cole makes it clear that Voodoo Vintners is not a guide to individual wines. Still, she obviously admires Bergstrom, Belle Pente, Beaux Freres and Brick House. (All "B"s, as is Burgundy! Woo-woo!) In the end, Cole seems content to introduce the reader to BD's practitioners and practices;

Voodoo Vintners is meant as a guided tour, not a manifesto. The faithful may complain that Cole lacks commitment, but the rest of us can agree that she gives us a great ride.

Voodoo Vintners, Oregon State University Press, 192 pages, $18.95

FRIULI, Italy--It hasn't been tried before, an international summit like this on the opportunities and challenges facing the country's

FRIULI, Italy--It hasn't been tried before, an international summit like this on the opportunities and challenges facing the country's